We recently gave a few pointers on how you can fine-tune Kafka producers to improve message publication to Kafka. Here we’re going to examine commonly-used tuning options that optimize how messages are consumed by Kafka consumers.

It is worthwhile considering both ends of the streaming pipeline. If you make your producer more efficient, you will want to calibrate your consumer to be able to accommodate those efficiencies. Or at least not be an impediment after the improvements you’ve made. As we shall see in this post, some consumer configuration is actually dependent on complementary producer and Kafka configuration.

How is your consumer performing?

When looking to optimize your consumers, you will certainly want to control what happens to messages in the event of failure. And you will also want to make sure, as far as possible, that you have scaled your consumer groups appropriately to handle the level of throughput you expect. As with producers, you will want to monitor the performance of your consumers before you start to make your adjustments. Think about the outcomes you expect from your consumers in terms of reliability and stability.

If you want to read more about performance metrics for monitoring Kafka consumers, see Kafka’s Consumer Fetch Metrics.

Basic consumer configuration

A basic consumer configuration must have a host:port bootstrap server address for connecting to a Kafka broker. It will also require deserializers to transform the message keys and values. A client id is advisable, as it can be used to identify the client as a source for requests in logs and metrics.

bootstrap.servers=localhost:9092

key.deserializer=org.apache.kafka.common.serialization.StringDeserializer

value.deserializer=org.apache.kafka.common.serialization.StringDeserializer

client.id=my-client

Key properties

On top of our minimum configuration, there are a number of properties you can use to fine-tune your consumer configuration. We won’t cover all possible consumer configuration options here, but examine a curated set of properties that offer specific solutions to requirements that often need addressing:

group.idfetch.max.wait.msfetch.min.bytesfetch.max.bytesmax.partition.fetch.bytesmax.message.bytes (topic or broker)enable.auto.commitauto.commit.interval.msisolation.levelsession.timeout.msheartbeat.interval.msauto.offset.resetgroup.instance.idmax.poll.interval.msmax.poll.records

We’ll look at how you can use a combination of these properties to regulate:

- Consumer scalability to accommodate increased throughput

- Throughput measured in the number of messages processed over a specific period

- Latency measured in the time it takes for messages to be fetched from the broker

- Data loss or duplication when committing offsets or recovering from failure

- Handling of transactional messages from the producer and consumer side

- Minimizing the impact of rebalances to reduce downtime

As with producers, you will want to achieve a balance between throughput and latency that meets your needs. You will also want to ensure your configuration helps reduce delays caused by unnecessary rebalances of consumer groups. Note, however, that you should avoid using any properties that cause conflict with the properties or guarantees provided by your application.

If you want to read more about what each property does, see Kafka’s consumer configs.

Message ordering guarantees

Kafka only provides ordering guarantees for messages in a single partition. If you want a strict ordering of messages from one topic, the only option is to use one partition per topic. The consumer can then observe messages in the same order that they were committed to the broker.

Potentially, things become less precise when a consumer is consuming messages from multiple partitions. Although the ordering for each partition is kept, the order of messages fetched from all partitions is not guaranteed, as it does not necessarily reflect the order in which they were sent. In practice, however, retaining the order of messages in each partition when consuming from multiple partitions is usually sufficient because messages whose order matters can be sent to the same partition (either by having the same key, or perhaps by using a custom partitioner).

Scaling with consumer groups

Consumer groups are used so commonly, that they might be considered part of a basic consumer configuration. Consumer groups are a way of sharing the work of consuming messages from a set of partitions between a number of consumers by dividing the partitions between them. Consumers are grouped using a group.id, allowing messages to be spread across the members that share the same id.

# ...

group.id=my-group-id

# ...

Consumer groups are very useful for scaling your consumers according to demand. Consumers within a group do not read data from the same partition, but can receive data exclusively from zero or more partitions. Each partition is assigned to exactly one member of a consumer group.

There are a couple of things worth mentioning when thinking about how many consumers to include in a group. Adding more consumers than partitions will not increase throughput. Excess consumers will be partition-free and idle. This might not be entirely pointless, however, as an idle consumer is effectively on standby in the event of failure of one of the consumers that does have partitions assigned.

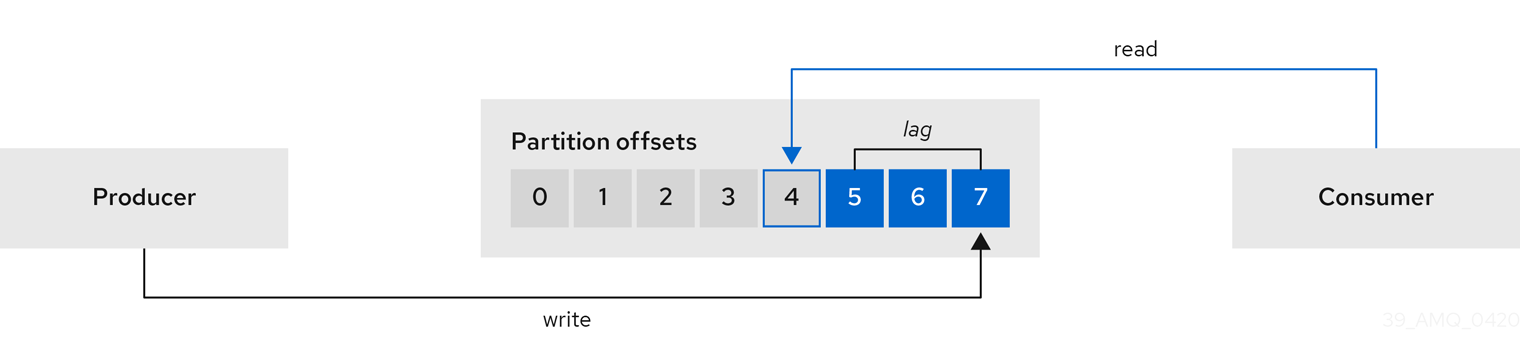

Consumer lag and consumer groups

For applications that rely on processing (near) real-time data, consumer lag is a vitally important metric. Consumer lag indicates the difference in the rate of production and consumption of messages. Specifically, consumer lag for a given consumer group indicates the delay between the last message added to a topic partition and the message last picked up by the consumer of that partition. If consumer lag is a problem, there are definite actions you can take to reduce it.

If the bottleneck is in the consumer processes and there are fewer consumers than partitions then adding more consumers to the consumer group subscribed to a topic should help. An important point to make here, though, is that consumer configuration tuning in isolation might not be sufficient to meeting your optimization goals.

Consumer lag growing continually is an indication that the consumer group cannot keep up with the rate of message production. If this happens for long enough, it is possible that the topic retention configurations might mean messages are deleted by the broker before they’re read by the consumer. In this case, a short term solution is to increase the retention.bytes or retention.ms of the topic, but this only puts off the inevitable. The longer term solution is to increase consumer throughput (or slow message production). A more common situation is where the workload is spiky, meaning the consumer lag grows and shrinks. This is only a problem to the extent that the consumer needs to be operating in (near) real time.

Improving throughput by increasing the minimum amount of data fetched in a request

Use the fetch.max.wait.ms and fetch.min.bytes configuration properties to set thresholds that control the number of requests from your consumer.

-

fetch.max.wait.msSets a maximum threshold for time-based batching. -

fetch.min.bytesSets a minimum threshold for size-based batching.

When the client application polls for data, both these properties govern the amount of data fetched by the consumer from the broker. You can adjust the properties higher so that there are fewer requests, and messages are delivered in bigger batches. You might want to do this if the amount of data being produced is low. Reducing the number of requests from the consumer also lowers the overhead on CPU utilization for the consumer and broker.

Throughput is improved by increasing the amount of data fetched in a batch, but with some cost to latency. Consequently, adjusting these properties lower has the effect of lowering end-to-end latency. We’ll look a bit more at targeting latency by increasing batch sizes in the next section.

You can use one or both of these properties. If you use both, Kafka will respond to a fetch request when the first of either threshold is reached.

# ...

fetch.max.wait.ms=500

fetch.min.bytes=16384

# ...

Lowering latency by increasing maximum batch sizes

Increasing the minimum amount of data fetched in a request can help with increasing throughput. But if you want to do something to improve latency, you can extend your thresholds by increasing the maximum amount of data that can be fetched by the consumer from the broker.

-

fetch.max.bytesSets a maximum limit in bytes on the amount of data fetched from the broker at one time -

max.partition.fetch.bytesSets a maximum limit in bytes on how much data is returned for each partition, which must always be larger than the number of bytes set in the broker or topic configuration formax.message.bytes.

By increasing the values of these two properties, and allowing more data in each request, latency might be improved as there are fewer fetch requests.

# ...

fetch.max.bytes=52428800

max.partition.fetch.bytes=1048576

# ...

Be careful with memory usage. The maximum amount of memory a client can consume is calculated approximately as:

NUMBER-OF-BROKERS * fetch.max.bytes and NUMBER-OF-PARTITIONS * max.partition.fetch.bytes

Avoiding data loss or duplication when committing offsets

For applications that require durable message delivery, you can increase the level of control over consumers when committing offsets to minimize the risk of data being lost or duplicated.

Kafka’s auto-commit mechanism is pretty convenient (and sometimes suitable, depending on the use case). When enabled, consumers commit the offsets of messages automatically every auto.commit.interval.ms milliseconds. But convenience, as always, has a price. By allowing your consumer to commit offsets, you are introducing a risk of data loss and duplication.

- Data loss If your application commits an offset, and then crashes before all the messages up to that offset have actually been processed, those messages won’t get processed when the application is restarted.

- Data duplication If your application has processed all the messages, and then crashes before the offset is committed automatically, the last offset is used when the application restarts and you’ll process those messages again.

If this potential situation leaves you slightly concerned, what can you do about it? First of all, you can use the auto.commit.interval.ms property to decrease those worrying intervals between commits.

# ...

auto.commit.interval.ms=1000

# ...

But this will not completely eliminate the chance that messages are lost or duplicated. Alternatively, you can turn off auto-committing by setting enable.auto.commit to false. You then assume responsibility for how your consumer application handles commits correctly. This is an important decision. Periodic automatic offset commits do mean it’s something you don’t need to worry about. And as long as all message processing is done before the next poll, all processed offsets will be committed. But a higher level of control might be preferable if data loss or data duplication is to be avoided.

# ...

enable.auto.commit=false

# ...

Having turned off the auto-commit, a more robust course of action is to set up your consumer client application to only commit offsets after all processing has been performed and messages have been consumed. You determine when a message is consumed. To do this, you can introduce calls to the Kafka commitSync and commitAsync APIs, which commit specified offsets for topics and partitions to Kafka.

-

commitSyncThecommitSyncAPI commits the offsets of all messages returned from polling. Generally, you call the API when you are finished processing all the messages in a batch, and don’t poll for new messages until the last offset in the batch is committed. This approach can can affect throughput and latency, as can the number of messages returned when polling, so you can set up your application to commit less fequently. -

commitAsyncThecommitAsyncAPI does not wait for the broker to respond to a commit request. ThecommitAsyncAPI has lower latency than thecommitSyncAPI, but risks creating duplicates when rebalancing.

A common approach is to capitalize on the benefits of using both APIs, so the lower latency commitAsync API is used by default, but the commitSync API takes over before shutting the consumer down or rebalancing to safeguard the final commit.

Turning off the auto-commit functionality helps with data loss because you can write your code to only commit offsets when messages have actually been processed. But manual commits cannot completely eliminate data duplication because you cannot guarantee that the offset commit message will always be processed by the broker. This is the case even if you do a synchronous offset commit after processing each message.

You can set up your Kafka solution to interact with databases that provide ACID (atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability) reliability guarantees to store consumer offsets.

Configuring a reliable data pipeline

To guarantee the reliability of message delivery on the producer side, you might configure your producers to use idempotence and transactional ids.

- Idempotence

- Idempotence properties used to guarantee the non-duplication and ordering of message delivery from producers for exactly once writes to a single partition.

# ... enable.idempotence=true max.in.flight.requests.per.connection=5 acks=all retries=2147483647 # ...

- Transactional id

- Transactional properties guarantee that messages using the same transactional is are produced once, and either all are successfully written to the respective logs or none of them are. The timeout set a time limit on achieving this.

# ... transactional.id=UNIQUE-ID transaction.timeout.ms=900000 # ...

With producers set up in such a way, you can make the pipeline more secure from the consumer side by introducing the isolation.level property. The isolation.level property controls how transactional messages are read by the consumer, and has two valid values:

read_committedread_uncommitted(default)

If you switch from the default to read_committed, only transactional messages that have been committed are read by the consumer. As always, there’s a trade-off. Using this mode will lead to an increase in end-to-end latency because the consumer will only return a message when the brokers have written the transaction markers that record the result of the transaction (committed or aborted).

# ...

enable.auto.commit=false

isolation.level=read_committed

# ...

Recovering from failure within a consumer group

You can define how often checks are made on the health of consumers within a consumer group. If consumers fail within a consumer group, a rebalance is triggered and partition ownership is reassigned to the members of the group. You want to get the timings of your checks just right so that the consumer group can recover quickly, but unnecessary rebalances are not triggered. And you use two properties to do it: session.timeout.ms and heartbeat.interval.ms.

-

session.timeout.msSpecifies the maximum amount of time in milliseconds a consumer within a consumer group can be out of contact with a broker before being considered inactive and a rebalancing is triggered between the active consumers in the group. Setting thesession.timeout.msproperty lower means failing consumers are detected earlier, and rebalancing can take place quicker. However, you don’t want to set the timeout so low that the broker fails to receive an heartbeat in time and triggers an unnecessary rebalance. -

heartbeat.interval.msSpecifies the interval in milliseconds between heartbeat checks to the consumer group coordinator to indicate that a consumer is active and connected. The heartbeat interval must be lower, usually by a third, than the session timeout interval. Decreasing the heartbeat interval according to anticipated rebalances reduces the chance of accidental rebalancing, but bear in mind that frequent heartbeat checks increase the overhead on broker resources.

# ...

heartbeat.interval.ms=3000

session.timeout.ms=10000

# ...

If the broker configuration specifies a

group.min.session.timeout.msandgroup.max.session.timeout.ms, thesession.timeout.msvalue must be within that range.

Managing offset policy

How should a consumer behave when no offsets have been committed? Or when a committed offset is no longer valid or deleted? If you set the auto.offset.reset property correctly, it should behave impeccably in both events.

Let’s first consider what should happen when no offsets have been committed. Suppose a new consumer application connects with a broker and presents a new consumer group id for the first time. Offsets determine up to which message in a partition a consumer has read from. Consumer offset information lives in an internal Kafka topic called __consumer_offsets. The __consumer_offsets topic does not yet contain any offset information for this new application. So where does the consumer start from? With the auto.offset.reset property set as latest, which is the default, the consumer will start processing only new messages. By processing only new messages, any existing messages will be missed. Alternatively, you can set the auto.offset.reset property to earliest and also process existing messages from the start of the log.

And what happens when offsets are no longer valid? If a consumer group or standalone consumer is inactive and commits no offsets during the offsets retention period (offsets.retention.minutes) configured for a broker, previously committed offsets are deleted from __consumer_offsets. Again, you can use the earliest option in this situation so that the consumer returns to the start of a partition to avoid data loss if offsets were not committed.

If the amount of data returned in a single fetch request is large, depending on the frequency in which the consumer client application polls for new messages, a timeout might occur before the consumer has processed it. In which case, you can lower max.partition.fetch.bytes or increase session.timeout.ms as part of your offset policy.

# ...

auto.offset.reset=earliest

session.timeout.ms=10000

max.partition.fetch.bytes=1048576

# ...

Minimizing the impact of rebalancing your consumer group

Rebalancing is the time taken to assign a partition to active consumers in a group. During a rebalance:

- Consumers commit their offsets

- A new consumer group is formed

- The designated group leader assigns partitions evenly to group members

- The consumers in the group receive their assignments and start to fetch data

Obviously, the rebalancing process takes time. And during a rolling restart of a consumer group cluster, it happens repeatedly. So rebalancing can have a clear impact on the performance of your cluster group. As mentioned, increasing the number of heartbeat checks reduces the likelihood of unnecessary rebalances. But there a couple more approaches you can take. One is to set up static membership to reduce the overall number of rebalances. Static membership uses persistence so that a consumer instance is recognized during a restart after a session timeout.

You can use the group.instance.id property to specify a unique group instance id for a consumer. The consumer group coordinator can then use the id when identifying a new consumer instance following a restart.

# ...

group.instance.id=UNIQUE-ID

# ...

The consumer group coordinator assigns the consumer instance a new member id, but as a static member, it continues with the same instance id and retains the same assignment of topic partitions.

Another cause of rebalancing might actually be due to an insufficient poll interval configuration, which is then interpreted as a consumer failure. If you discover this situation when examining your consumer logs, you can calibrate the max.poll.interval.ms and max.poll.interval.ms polling configuration properties to reduce the number of rebalances.

-

max.poll.interval.msSets the interval to check the consumer is continuing to process messages. If the consumer application does not make a call to poll at least everymax.poll.interval.msmilliseconds, the consumer is considered to be failed, causing a rebalance. If the application cannot process all the records returned from poll in time, you can avoid a rebalance by using this property to increase the interval in milliseconds between polls for new messages from a consumer. -

max.poll.recordsSets the number of processed records returned from the consumer. You can use themax.poll.recordsproperty to set a maximum limit on the number of records returned from the consumer buffer, allowing your application to process fewer records within themax.poll.interval.mslimit.

# ...

group.instance.id=UNIQUE-ID

max.poll.interval.ms=300000

max.poll.records=500

# ...

Changing your consumer habits

So that was a brief run through some of the most frequently used configuration options. Any strategy you choose to adopt will always have to take into account the other moving parts – the intended functionality of your consumer client application, the broker architecture, and the producer configuration. For example, if you are not using transactional producers, then there’s no point in setting the isolation.level property. But it is unlikely that there’s nothing you can do to make your consumers run better. And the consumer configuration options are available exactly for that reason.

RELATED POSTS