Apache Kafka is a distributed streaming platform that allows efficient and reliable processing of messages. It is widely used in various industries for data streaming applications, such as processing real-time data, event sourcing, and microservices integration. One of the key features of Kafka is the support for transactions, which provides exactly-once semantics (EOS) and is available since Kafka 0.11 (KIP-98). The support for EOS was recently extended to source connectors in Kafka Connect, which enables configuration-driven and fully transactional streaming pipelines (KIP-618).

Transactions provide the guarantee of atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability (ACID) for a group of messages that are published to Kafka. This means that either all messages within the transaction will be successfully written to Kafka or none of the messages will be written. This is a crucial feature when it comes to ensuring data consistency and avoiding any data loss.

Kafka transactions are particularly important in scenarios where data integrity is critical, such as financial transactions and logging systems. Additionally, using Kafka transactions can help ensure that the ordering of events is preserved, which can be necessary for certain applications.

In this post you will learn how EOS works in Kafka, which are the main components that are involved in a transaction lifetime and their requirements. Then, you will learn about the drawbacks, so that you can anticipate any issue long before your application reaches production stage. Finally, you will see a basic example that helps to understand how transactions metadata are stored, which is useful for troubleshooting.

A general understanding of how the log replication protocol works is required to fully understand some of the concepts presented here.

Delivery guarantees

In distributed systems like Kafka, any component can fail independently and you have to deal with this fact. For example, a broker may crash or a network failure may happen while the producer is sending a message to a topic.

Depending on the configuration and application logic, you can have three different delivery semantics:

- at-most-once: the producer does not retry when there is a timeout or error (data loss risk)

- at-least-once: the producer retries but the broker can fail after writing but before sending the ack (duplicate messages risk)

- exactly-once: even if the producer retries sending a message, it is written exactly once (idempotency)

With at-least-once, there is no way for the producer to know the nature of the failure, so it simply assumes that the message was not written and retries. There are use cases in which lost or duplicated messages are acceptable, but in others this would cause serious business problems (e.g. a duplicate debit from a bank account).

To be fair, there is no such thing as exactly-once delivery in distributed systems (two generals’ problem), but we can fake it by implementing idempotent log append. Another way to achieve EOS is to apply a deduplication logic at the consumer side, but this is a stateful logic that needs to be replicated in every consumer.

Idempotence is the property of certain operations in mathematics and computer science whereby they can be applied multiple times without changing the result beyond the initial application.

Since Kafka 3.0, the producer enables the stronger delivery guarantees by default (acks=all, enable.idempotence=true).

In addition to durability, this provides partition level message ordering and duplicates protection.

When the idempotent producer is enabled, the broker registers a producer id (PID) for every new producer instance.

A sequence number is assigned to each record when the batch is first added to a produce request and never changed, even if the batch is resent.

The broker keeps track of the sequence number per producer and partition, periodically storing this information in a .snapshot file.

Whenever a new batch arrives, the broker checks if the received sequence number is equal to the last-appended batch’s sequence number plus one, then the batch is acknowledged, otherwise it is rejected.

Unfortunately, the idempotent producer does not guarantee duplicate protection across restarts and when you need to write to multiple partitions as a single unit of work. This is the typical scenario with many stream processing applications that run read-process-write cycles. In this case, you can make these cycles atomic using the transaction support of the Kafka Producer or Kafka Streams APIs.

The transaction support exposed by the Producer API is low level, and needs to be used carefully in order to actually get transactional semantics.

For those using Kafka Streams it is much simpler: setting processing.guarantee=exactly_once_v2 will enable EOS on your existing topology.

Considerations

Each producer must configure its own static and unique transactional.id.

The transactional.id is used to uniquely identify the same logical producer across process restarts.

In contrast to the idempotent producer, a transactional producer instance will be allocated the same PID (but incremented producer epoch), as any previous instance with the same transactional.id.

Together the PID and producer epoch identify a logical producer session.

Before Kafka 2.6 the

transactional.idhad to be a static encoding of the input partitions in order to avoid ownership transfer between application instances during rebalances, that would invalidate the fencing logic. This limitation was hugely inefficient, because an application instance couldn’t reuse a single thread-safe producer instance, but had to create one for each input partition. It was fixed by forcing the producer to send the consumer group metadata along with the offsets to commit (KIP-447).

When starting, the client application calls Producer.initTransactions to initialize the producer session, allowing the broker to tidy up state associated with any previous incarnations of this producer, as identified by the transactional.id.

Thereafter, any existing producers using the same transactional.id are considered zombies, and are fenced off as soon as they try to send data.

To guarantee message ordering, a given producer can have at most one ongoing transaction (they are executed serially).

Brokers will prevent consumers with isolation.level=read_committed from advancing to offsets which include open transactions.

Messages from aborted transactions are filtered out within the consumer, and are never observed by the client application.

It is important to note that transactions are only supported inside a single Kafka cluster. If the transaction scope includes processors with externally observable side-effects, you would need to use additional components. The transactional outbox pattern could help in this case.

Transaction metadata

In order to implement transactions Kafka brokers need to include extra book-keeping information in logs.

Information about producers and their transactions is stored in the __transaction_state topic which is used by a broker component called the transaction coordinator.

Each transaction coordinator owns a subset of the partitions in this topic (i.e. the partitions for which its broker is the leader).

Within user logs in addition to the usual batches of data records, transaction coordinators cause partition leaders to append control records (commit/abort markers) for tracking which batches have actually been committed and which rolled back. Control records are not exposed to applications by Kafka consumers, as they are an internal implementation detail of the transaction support.

Non-transactional records are considered decided immediately, but transactional records are only decided when the corresponding commit or abort marker is written.

A transaction goes through the following states:

- Undecided (Ongoing)

- Decided and unreplicated (PrepareCommit|PrepareAbort)

- Decided and replicated (CompleteCommit|CompleteAbort)

This is handled through a process similar to the two-phase commit protocol, where the state is tracked by a series of control records witten to __transaction_state topic.

Every time some data is written to a new partition inside a transaction, we have the Ongoing state, which includes the list of involved partitions.

When the transaction completes, we have the PrepareCommit or PrepareAbort state change.

Once the control record is written to each involved partition, we have the CompleteCommit or CompleteAbort state change.

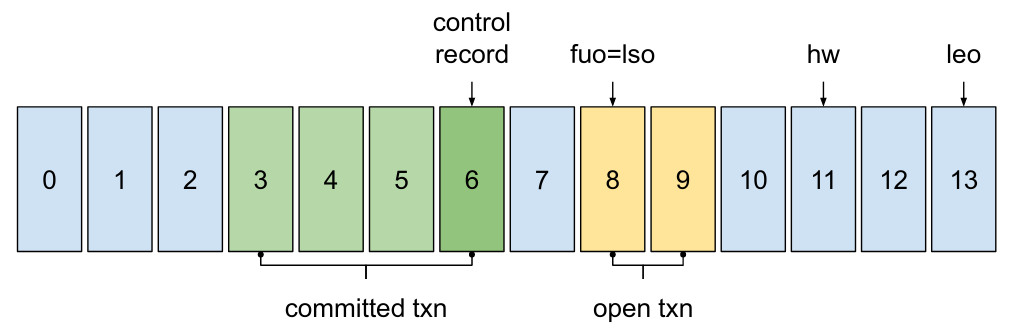

The last stable offset (LSO) is the offset in a user partition such that all lower offsets have been decided and it is always present. The first unstable offset (FUO) is the earliest offset in a user partition that is part of the ongoing transaction, if present. The high watermark (HW) is the offset of the last message that was successfully copied to all of the log’s in-sync replicas. The log end offset (LEO) is the the highest offset of the partition.

We have that LSO <= HW <= LEO, which can be the same offset when there is no open transaction and all partitions are in-sync.

Performance

There are a few drawbacks when using Kafka transactions that developers should be aware of.

Firstly, enabling EOS has an effect on throughput, which can be significant. Each producer can only process transactions sequentially, so you might need multiple transactional producers, which can have a knock-on effect on the rest of the application. This is where frameworks can provide useful abstractions over multiple producer instances.

Then, transactions can add some latency to an application due to the write amplification required to ensure EOS. While this may not be a significant issue for some applications, those that require real-time processing may be affected.

Each transaction incurs some overhead that is independent of the number of messages involved. This overhead includes the following:

- A small number of Remote Procedure Calls (RPCs) to register the partitions with the coordinator (these RPCs can be batched together to reduce overhead).

- A transaction marker record that must be written to each involved partition when the transaction is completed.

- A few state change records that are appended to the internal transaction state log.

Most of this latency is on the producer side, where the transactions API is implemented. The consumer is only be able to fetch up to the LSO, but it has to buffer records in memory until the commit marker is observed, so you have increased memory usage.

The performance degradation can be significant when having short transaction commit intervals. Increasing the transaction duration also increases the end-to-end latency and may require some additional tuning, so it’s a matter of tradeoff.

Hanging transactions

Hanging transactions have a missing or out-of-order control record and may be caused by delayed messages due to a network issue (KIP-890). This issue is rare, but it’s important to be aware and set alerts, because the consequences can impact the service availability.

The transaction coordinator automatically aborts any ongoing transaction that is not completed within transaction.timeout.ms.

This mechanism does not work for hanging transactions because from the coordinator’s point of view the transaction was completed and a transaction marker written (and no longer needs to be timed out).

But from the partition leader’s point of view there is a data record for a transaction after the commit/abort marker, which is indistinguishable from the start of a new transaction.

A hanging transaction is usually revealed by a stuck application with growing lag. Despite messages being produced, consumers can’t make any progress because the LSO does not grow anymore.

For example, you will see the following messages in the consumer logs:

[Consumer clientId=my-client, groupId=my-group] The following partitions still have unstable offsets which are not cleared on the broker side: [__consumer_offsets-27],

this could be either transactional offsets waiting for completion, or normal offsets waiting for replication after appending to local log

Additionally, if the partition belongs to a compacted topic, this causes the unbounded partition growth, because the LogCleaner does not clean beyond the LSO.

If not detected and fixed in time, this may lead to disk space exhaustion and service disruption.

Fortunately, there are embedded tools that can be used to find all hanging transactions and roll them back (KIP-664). When doing that, it is important to understand the business context surrounding the records in this transaction and possibly append those records again using a new transaction.

# find all hanging transactions in a broker

$ $KAFKA_HOME/bin/kafka-transactions.sh --bootstrap-server :9092 find-hanging --broker 0

Topic Partition ProducerId ProducerEpoch StartOffset LastTimestamp Duration(s)

__consumer_offsets 27 171100 1 913095344 2022-06-06T03:16:47Z 209793

# abort an hanging transaction

$ $KAFKA_HOME/bin/kafka-transactions.sh --bootstrap-server :9092 abort --topic __consumer_offsets --partition 27 --start-offset 913095344

Authorization

The TransactionalIdAuthorizationException happens when you have authorization enabled without the appropriate ACLs rules.

In the following example we allow any transactional.id from any user.

$ $KAFKA_HOME/bin/kafka-acls.sh --bootstrap-server :9092 --command-config client.properties --add \

--allow-principal User:* --operation write --transactional-id *

Error handling

If any of the send operations inside the transaction scope fails, the final Producer.commitTransaction will fail and throw the exception from the last failed send.

When this happens, your application should call Producer.abortTransaction to reset the state and apply a retry strategy.

Unlike other exceptions thrown from the producer, ProducerFencedException, FencedInstanceIdException and OutOfOrderSequenceException cannot be recovered.

The application should catch these exceptions, close the current producer instance and create a new one.

When running on a Kubernetes platform, another option could be to simply shutdown and let the platform restart the application.

Monitoring

It is important to collect metrics provided by your Kafka deployments.

If you’ve not collected the metrics then you have no information to go on when something goes wrong. You’re often left with no choice but to reconfigure with the right metrics and wait for the problem to happen again in order to understand it. This could double its impact, or worse.

On the broker side, the following JMX metrics are particularly helpful when diagnosing issue impacting transactions.

# requests: FindCoordinator, InitProducerId, AddPartitionsToTxn, Produce, EndTxn

kafka.network:type=RequestMetrics,name=RequestsPerSec,request=([\w]+)

kafka.network:type=RequestMetrics,name=RequestQueueTimeMs,request=([\w]+)

kafka.network:type=RequestMetrics,name=TotalTimeMs,request=([\w]+)

kafka.network:type=RequestMetrics,name=LocalTimeMs,request=([\w]+)

kafka.network:type=RequestMetrics,name=RemoteTimeMs,request=([\w]+)

kafka.network:type=RequestMetrics,name=ThrottleTimeMs,request=([\w]+)

kafka.network:type=RequestMetrics,name=ResponseQueueTimeMs,request=([\w]+)

kafka.network:type=RequestMetrics,name=ResponseSendTimeMs,request=([\w]+)

# attributes: Count, 99thPercentile

Likewise the following producer metrics can be helpful, perhaps after broker logs reveal some misbehavior.

kafka.producer:type=producer-metrics,client-id=([-.\w]+)

# attributes: txn-init-time-ns-total, txn-begin-time-ns-total, txn-send-offsets-time-ns-total, txn-commit-time-ns-total, txn-abort-time-ns-total

Basic example

Let’s run a basic example to see how transactions work at the partition level. You just need an environment with few command line tools (curl, tar, java, mvn).

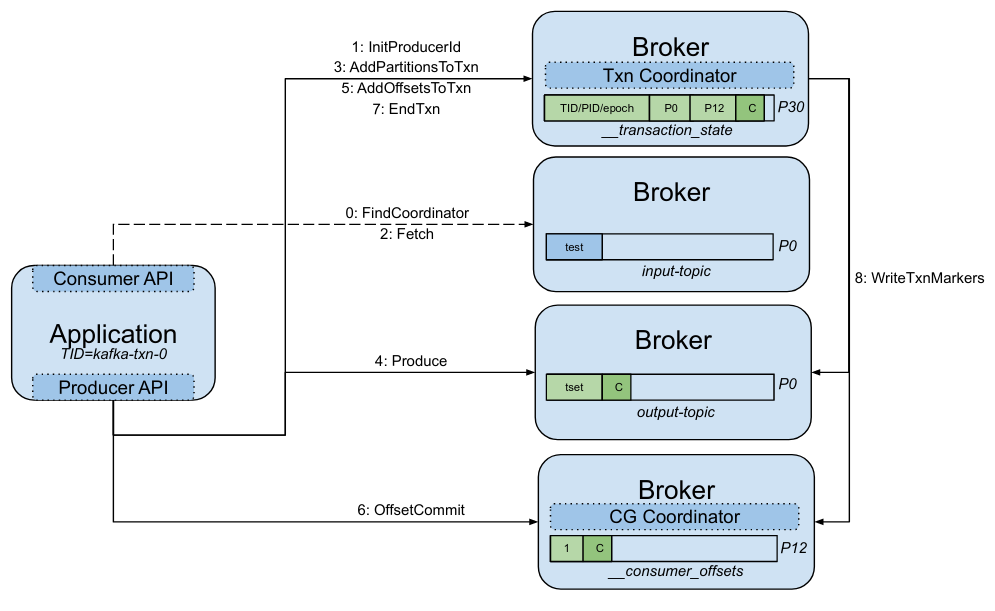

This application consumes text messages from the input-topic, reverses their content, and sends the result to the output-topic.

All of this happens as part of single atomic operation, which also includes committing the consumer offsets.

The following diagram shows the relevant RPCs.

In the following snippet we start the Kafka cluster, run the application, and create a single transaction. For the sake of simplicity, we use a single-node cluster running on localhost, but the example also works with a multi-node cluster.

# download the Apache Kafka binary and start a single-node Kafka cluster in background

$ KAFKA_VERSION="3.4.0" KAFKA_HOME="$(mktemp -d -t kafka.XXXXXXX)" && export KAFKA_HOME

$ curl -sLk "https://archive.apache.org/dist/kafka/$KAFKA_VERSION/kafka_2.13-$KAFKA_VERSION.tgz" \

| tar xz -C "$KAFKA_HOME" --strip-components 1

$ $KAFKA_HOME/bin/zookeeper-server-start.sh -daemon $KAFKA_HOME/config/zookeeper.properties \

&& sleep 5 && $KAFKA_HOME/bin/kafka-server-start.sh -daemon $KAFKA_HOME/config/server.properties

# open a new terminal, get and run the application (Ctrl+C to stop)

$ git clone git@github.com:fvaleri/examples.git -n --depth=1 --filter=tree:0 && cd examples \

&& git sparse-checkout set --no-cone kafka/kafka-txn && git checkout 957981f5d8ede82a265f695d9a10c83a50af718f

...

HEAD is now at 957981f Only reset affected partitions

$ export BOOTSTRAP_SERVERS="localhost:9092" INSTANCE_ID="kafka-txn-0" \

GROUP_ID="my-group" INPUT_TOPIC="input-topic" OUTPUT_TOPIC="output-topic"

$ mvn clean compile exec:java -q -f kafka/kafka-txn/pom.xml

Starting instance kafka-txn-0

Created topics: input-topic

Waiting for new data

...

# come back to the previous terminal and send a test message

$ $KAFKA_HOME/bin/kafka-console-producer.sh --bootstrap-server :9092 --topic input-topic

>test

>^C

All of this is pretty normal, but now comes the interesting part.

How can we identify which partitions are involved in this transaction and inspect their content?

We are writing to the output-topic which has only one partition, but the two internal topics have 50 partitions each by default.

To avoid looking at 100 partitions in the worst case, we can use the same hashing function that Kafka uses to find the coordinating partition.

This function maps group.id to __consumer_offsets partition, and transactional.id to __transaction_state partition.

$ kafka-cp() {

local id="${1-}" part="${2-50}"

if [[ -z $id ]]; then echo "Missing id parameter" && return; fi

echo 'public void run(String id, int part) { System.out.println(abs(id.hashCode()) % part); }

private int abs(int n) { return (n == Integer.MIN_VALUE) ? 0 : Math.abs(n); }

run("'"$id"'", '"$part"');' | jshell -

}

# applications offsets are in partition 12 of __consumer_offsets

$ kafka-cp my-group

12

# transaction states are in partition 30 of __transaction_state

$ kafka-cp kafka-txn-0

30

Knowing the output-topic and coordinating partitions, we can take a look at their content using the embedded dump tool.

Note how we pass the decoder parameter when dumping from internal topics, whose content is encoded for performance reasons.

1 # dump output-topic-0

2 $ $KAFKA_HOME/bin/kafka-dump-log.sh --deep-iteration --print-data-log --files /tmp/kafka-logs/output-topic-0/00000000000000000000.log

3 Dumping /tmp/kafka-logs/output-topic-0/00000000000000000000.log

4 Log starting offset: 0

5 baseOffset: 0 lastOffset: 0 count: 1 baseSequence: 0 lastSequence: 0 producerId: 0 producerEpoch: 0 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: true isControl: false deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 0 CreateTime: 1680383687941 size: 82 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 2785707995 isvalid: true

6 | offset: 0 CreateTime: 1680383687941 keySize: -1 valueSize: 14 sequence: 0 headerKeys: [] payload: tset

7 baseOffset: 1 lastOffset: 1 count: 1 baseSequence: -1 lastSequence: -1 producerId: 0 producerEpoch: 0 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: true isControl: true deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 82 CreateTime: 1680383688163 size: 78 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 3360473936 isvalid: true

8 | offset: 1 CreateTime: 1680383688163 keySize: 4 valueSize: 6 sequence: -1 headerKeys: [] endTxnMarker: COMMIT coordinatorEpoch: 0

9

10 # dump __consumer_offsets-12 using the offsets decoder

11 $ $KAFKA_HOME/bin/kafka-dump-log.sh --deep-iteration --print-data-log --offsets-decoder --files /tmp/kafka-logs/__consumer_offsets-12/00000000000000000000.log

12 Dumping /tmp/kafka-logs/__consumer_offsets-12/00000000000000000000.log

13 Starting offset: 0

14 ...

15 baseOffset: 1 lastOffset: 1 count: 1 baseSequence: 0 lastSequence: 0 producerId: 0 producerEpoch: 0 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: true isControl: false deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 339 CreateTime: 1665506597950 size: 118 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 4199759988 isvalid: true

16 | offset: 1 CreateTime: 1680383688085 keySize: 26 valueSize: 24 sequence: 0 headerKeys: [] key: offset_commit::group=my-group,partition=input-topic-0 payload: offset=1

17 baseOffset: 2 lastOffset: 2 count: 1 baseSequence: -1 lastSequence: -1 producerId: 0 producerEpoch: 0 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: true isControl: true deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 457 CreateTime: 1665506597998 size: 78 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 3355926470 isvalid: true

18 | offset: 2 CreateTime: 1665506597998 keySize: 4 valueSize: 6 sequence: -1 headerKeys: [] endTxnMarker: COMMIT coordinatorEpoch: 0

19 ...

The consumer offsets and the output message are committed (lines 8 and 18).

In wc-output-0 dump, we see that the data batch is transactional and contains the producer session (line 5).

In __consumer_offsets-12 dump, we have the consumer group’s offset commit record (line 16).

We can also look at how the transaction states are stored. These metadata are different from the transaction markers seen above, and they are only used by the transaction coordinator.

1 # dump __transaction_state-30 using the transaction log decoder

2 $KAFKA_HOME/bin/kafka-dump-log.sh --deep-iteration --print-data-log --transaction-log-decoder --files /tmp/kafka-logs/__transaction_state-30/00000000000000000000.log

3 Dumping /tmp/kafka-logs/__transaction_state-30/00000000000000000000.log

4 Log starting offset: 0

5 baseOffset: 0 lastOffset: 0 count: 1 baseSequence: -1 lastSequence: -1 producerId: -1 producerEpoch: -1 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: false isControl: false deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 0 CreateTime: 1680383478420 size: 122 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 2867569944 isvalid: true

6 | offset: 0 CreateTime: 1680383478420 keySize: 17 valueSize: 37 sequence: -1 headerKeys: [] key: transaction_metadata::transactionalId=kafka-txn-0 payload: producerId:0,producerEpoch:0,state=Empty,partitions=[],txnLastUpdateTimestamp=1680383478418,txnTimeoutMs=60000

7 baseOffset: 1 lastOffset: 1 count: 1 baseSequence: -1 lastSequence: -1 producerId: -1 producerEpoch: -1 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: false isControl: false deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 122 CreateTime: 1680383687954 size: 145 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 3735151334 isvalid: true

8 | offset: 1 CreateTime: 1680383687954 keySize: 17 valueSize: 59 sequence: -1 headerKeys: [] key: transaction_metadata::transactionalId=kafka-txn-0 payload: producerId:0,producerEpoch:0,state=Ongoing,partitions=[output-topic-0],txnLastUpdateTimestamp=1680383687952,txnTimeoutMs=60000

9 baseOffset: 2 lastOffset: 2 count: 1 baseSequence: -1 lastSequence: -1 producerId: -1 producerEpoch: -1 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: false isControl: false deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 267 CreateTime: 1680383687961 size: 174 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 3698066654 isvalid: true

10 | offset: 2 CreateTime: 1680383687961 keySize: 17 valueSize: 87 sequence: -1 headerKeys: [] key: transaction_metadata::transactionalId=kafka-txn-0 payload: producerId:0,producerEpoch:0,state=Ongoing,partitions=[output-topic-0,__consumer_offsets-12],txnLastUpdateTimestamp=1680383687960,txnTimeoutMs=60000

11 baseOffset: 3 lastOffset: 3 count: 1 baseSequence: -1 lastSequence: -1 producerId: -1 producerEpoch: -1 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: false isControl: false deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 441 CreateTime: 1680383688149 size: 174 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 1700234506 isvalid: true

12 | offset: 3 CreateTime: 1680383688149 keySize: 17 valueSize: 87 sequence: -1 headerKeys: [] key: transaction_metadata::transactionalId=kafka-txn-0 payload: producerId:0,producerEpoch:0,state=PrepareCommit,partitions=[output-topic-0,__consumer_offsets-12],txnLastUpdateTimestamp=1680383688148,txnTimeoutMs=60000

13 baseOffset: 4 lastOffset: 4 count: 1 baseSequence: -1 lastSequence: -1 producerId: -1 producerEpoch: -1 partitionLeaderEpoch: 0 isTransactional: false isControl: false deleteHorizonMs: OptionalLong.empty position: 615 CreateTime: 1680383688180 size: 122 magic: 2 compresscodec: none crc: 3020616838 isvalid: true

14 | offset: 4 CreateTime: 1680383688180 keySize: 17 valueSize: 37 sequence: -1 headerKeys: [] key: transaction_metadata::transactionalId=kafka-txn-0 payload: producerId:0,producerEpoch:0,state=CompleteCommit,partitions=[],txnLastUpdateTimestamp=1680383688154,txnTimeoutMs=60000

In __transaction_state-30 dump, we can see all state changes keyed by transactionalId (lines 6, 8, 10, 12, 14).

The transaction starts in Empty state, then we have Ongoing state for every new partition and finally PrepareCommit and CompleteCommit states when the commit is called.

Conclusion

Kafka transactions provide an essential means of ensuring data reliability and integrity, making them a crucial feature of the Kafka platform. However, these advantages come at the cost of reduced throughput and additional latency, which may require some tuning. If not monitored, hanging transactions can have an impact on the service availability.